For more information on the current projects going on in our lab, please go to the following link :

http://www.mcgill.ca/social-intelligence/

As of this past summer we have a new article in press at the journal Contemporary Educational Psychology, and we will give an overview of the study which was conducted at adult education centers.Worries and concerns regarding social rejection can be highly stressful and disruptive. In the school context in particular, such concerns and distractions can undermine confidence and interfere with performance. We therefore attempted to train a particular cognitive habit, of inhibiting thoughts of rejection, to see if this might help students deal with failure and social rejection. The participants were 150 students from adult education centers. They were first trained using our computer game which was designed to help them practice disengaging from images of socially-threatening faces, and focusing their attention on socially-supportive faces. Afterwards they were put in a difficult task situation where they underwent failure and social rejection. The results showed playing the find-the-smile “Matrix” game (as opposed to a control condition in which participants searched for nonsocial stimuli) was helpful to people; particularly those starting the study with relatively low self-esteem. The attentional training led them to feel less rejected and, on a computerized reaction-time task, they were less distracted by rejection-related stimuli. Also, participants who played the find-the-smile “Matrix” game reported fewer interfering thoughts about rejection while they were working on a school-related task, and went on to showed higher self-esteem scores after that task. These results show the potential for “emotion training” in serious games. More specifically, the findings demonstrate the value of research into the development of games to train attentional responses to social feedback, a cognitive habit that appears to yield beneficial emotional outcomes in the school context.

The article will be published later in the year, as: Dandeneau, S. D., & Baldwin, M.W., The buffering effects of rejection-inhibiting attentional training on social and performance threat among adult students. Contemporary Educational Psychology (2008)

Inside Self-Esteem Games

Our Book in Preparation – Send us your observations and stories!

We’re in the process of writing a book on self-esteem and habits of thought, and we would appreciate your help! We are hoping to gather together people’s stories, anecdotes, and observations about self-esteem. Our plan is to organize them around some of the major questions being studied by psychologists, for example:

“Where do high and low self-esteem come from?”

“Why does low self-esteem feel so bad?”

“What habits of thought are involved in low and high self-esteem?”

"How do different types of relationships affect self-esteem, and vice versa?"

We will then publish them, along with reviews of recent scientific research, in a book and on our website, for others to read about. If you have an observation about any aspect of self-esteem, or a story to tell, we would love to hear from you using a special form on our website. Anything from one sentence to a half-page would be happily received. All submissions will be anonymous. Thanks!

Here is a link to the form, with additional information:

www.selfesteemgames.mcgill.ca/research/stories.htm

Eye Spy: The Matrix

In feedback to us several people raised the question of whether the effects of playing our games would extend into “real life,” or might be limited to very short term effects in the laboratory. To test this question we asked working people to do the Eye Spy exercise every workday morning for five minutes, over a 5 day period. People who started the week with low self-esteem were most helped by the game – by the end of the week their self-esteem was almost as high as that of people who started out with high self-esteem. We are encouraged by these findings. We are preparing an article reporting these results for publication, and we plan to continue testing the games in a real-world context.

Wham! Self-Esteem Conditioning Game

We are currently collecting data for a new study on the effects of the Wham! Self-Esteem Conditioning Game among children aged 10-14. In this study we are using drawings of faces showing smiles and frowns. Preliminary analyses show that children who play Wham! show higher levels of self-liking compared to children who play a placebo version of the game.Online Research

During the summer, we launched our first online study in which nearly 600 people participated! The study looked at the relationship between self-esteem, attachment, and internal models of the self and other. We are very appreciative of the overwhelming interest and support we had for this study. The study was just recently completed, and we plan to post our findings on the website in February. A very big THANK YOU to everyone who participated in this study!

In the coming weeks and months we plan to launch more online research, so if you feel like participating in self-esteem science, check the website periodically.

Conference PresentationsAt the end of January the Self-Esteem Games team will be presenting findings from our most recent studies at the annual conference of the Society for Personality and Social Psychology in New Orleans, USA.

Thanks, and best wishes for a happy 2005!

Inside Self-Esteem Games

Thank you!

Thank you to everyone who has visited our website, sent us feedback, and signed up for our email list! Thanks also to all who brought to our attention the coverage our research has been getting in the online media, from ABCnews.com to Spiegel to the BBC and The Hindu. More stories are coming out soon in Business Week and Health magazines. The response has truly been overwhelming and we are very happy that so many people are interested in our research, and our games.

Eye Spy: The Matrix

We’re listening! Many people commented on the fact that the faces in Eye Spy were not randomized. Well we’ve fixed that! We’ve also added some feedback to the end of the game telling you how long it took you to complete. Try out the new version of the game here.

Wham! Self-Esteem Conditioning Game

Several people mentioned that some of the “other” information paired with frowning faces was their own (e.g. for people named “George” or “Margaret”) or significant to them (e.g. their daughter’s birthday). We are looking into ways to deal with this issue and hope to fix it in the near future. For now, we’ve corrected the programming so that if YOUR name/birthday happens to be one of the “other” names/birthdays it will no longer be paired with a frowning face. We’ve also added feedback information at the end of the game to help you improve! Try out the new version of the game here.

Grow Your Chi

The Grow Your Chi game still has a few bugs in it and we are grateful to everyone who has brought many of them to our attention! We’re hoping to fix these shortly.

Things to Watch Out For

We’re in the process of updating of database of faces! We hope to be able to provide a separate group of faces for each of our three games.

We have started to launch some ONLINE RESEARCH! If you feel like participating in self-esteem science, click here.

Can computer games help raise self-esteem? Absolutely. In a world-first study, researchers from McGill University’s Department of Psychology have created and tested computer games that are specifically designed to help people enhance their self-acceptance.

May 6, 2004

Source: Sylvain-Jacques Desjardins

Communications officer, University Relations Office,

514-398-6752, sylvain-jacques.desjardins@mcgill.ca

Contact: Mark W. Baldwin, Department of Psychology,

514-398-6090, mbaldwin AT ego.psych.mcgill.caPlaying games for self-esteem

McGill scientists design world-first: computer games that enhance self-acceptanceCan computer games help raise self-esteem? Absolutely. In a world-first study, researchers from McGill University’s Department of Psychology have created and tested computer games that are specifically designed to help people enhance their self-acceptance.

Available for public consultation at www.selfesteemgames.mcgill.ca, the games have catchy names such as Wham!, EyeSpy: The Matrix and Grow Your Chi. All three games were developed by doctoral students from McGill’s Department of Psychology: Jodene Baccus, Stéphane Dandeneau and Maya Sakellaropoulo, under the direction and supervision of Mark Baldwin, an associate psychology professor.

The team’s first research results on Wham! will be published in the peer-reviewed journal, Psychological Science in July. Publication of research on EyeSpy: The Matrix is forthcoming in the Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology. (Please see attached for further game and study descriptions).

Research goals

After examining past studies on self esteem, the McGill team deduced that people’s feelings of insecurity are largely based on worries about whether they will be liked, accepted and valued by their peers and significant others.Research has also shown that self-esteem is strongly influenced by particular ways of thinking. Self-esteem difficulties arise from people’s self-critical views concerning their characteristics and performances, along with an assumption that others will reject them. Comparatively, people who are more secure have a range of automatic thought processes that make them confident and buffer them from worrying about the possibility of social rejection.

“For people with low self-esteem, negative thought patterns occur automatically and often involuntarily,” explains Baldwin, “leading them to selectively focus their attention on failures and rejections.” The solution? People with ‘automatic’ negative personal outlooks need to condition their minds towards positive views and learn to be more accepting of themselves. The McGill team’s goal was to conduct experimental research that would enable them to develop interventions that could help people feel more secure: i.e. specially designed computer games.

The games people can play

“The three games work by addressing the underlying thought processes that increase self-liking,explains Baldwin. “As athletes know, to learn any new habit takes a lot of practice. Our team wanted to create a new way to help people practice the desired thought patterns to the point of being automatic.”

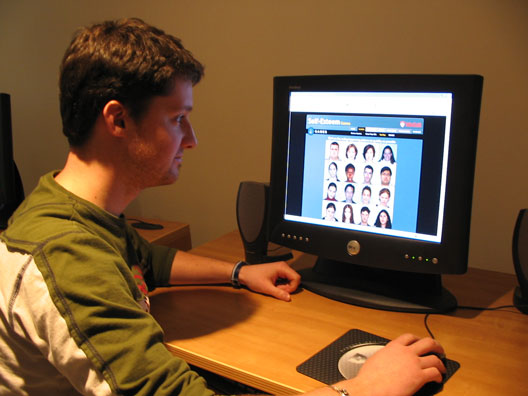

The researchers drew on their experience playing repetitive computer games and devised novel counterparts that would help people feel more positive about themselves. In the first computer game, EyeSpy: The Matrix, players are asked to search for a single smiling face in a matrix of 15 frowning faces. The hypothesis? Repeating the exercise can train players to focus their attention on positive rather than negative feedback.

The second game, Wham!, was built on Pavlov's well-known conditioning research.The Wham game has players register their name and birthday. Once the game is in action, the player’s personal information is paired with smiling, accepting faces. The outcome? Players have experiences similar to being smiled at by everyone and take on a more positive attitude about themselves.

For the third game, Grow Your Chi, the researchers combined the tasks of Wham! and EyeSpy: The Matrix. Players of Grow Your Chi try to nurture their inner source of well-being by responding to positive versus negative social information.

Practice improves positive outlook

The McGill team has demonstrated that with enough practice, even people with low self-esteem can develop positive thought patterns that may allow them to gradually become more secure and self-confident. That’s why everyone is encouraged to sample www.selfesteemgames.mcgill.ca and to see for themselves how the online exercise can effect positive change. “We are now starting to examine the possible benefits of playing these games every day,” says Baldwin. “We plan to study whether these kinds of games will be helpful to schoolchildren, salespeople dealing with job-related rejection and perhaps people on the dating scene.”Despite the potential benefits of these games, poor self-esteem remains an incredibly complex issue. "These games do not replace the hard work of psychotherapy,” Baldwin stresses. “Our findings, however, provide hope that a new set of techniques can gradually be developed to help people as they seek to overcome low self-esteem and feelings of insecurity."

-30-

Reporters are welcome to use the images from this page.

In a world-first, researchers from McGill University’s Department of Psychology have developed and tested computer games that can actually help people enhance their self-acceptance. Read on for brief facts concerning the studies that will be published in Psychological Science and the Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology.

May 6, 2004

Source: Sylvain-Jacques Desjardins

Communications officer, University Relations Office,

514-398-6752, sylvain-jacques.desjardins@mcgill.ca

Contact: Mark W. Baldwin, Department of Psychology,

514-398-6090, mbaldwin AT ego.psych.mcgill.caComputer Games that help boost self-esteem

Details behind Wham! and EyeSpy: The MatrixIn a world-first, researchers from McGill University’s Department of Psychology have developed and tested computer games that can actually help people enhance their self-acceptance. Read on for brief facts concerning the studies that will be published in Psychological Science and the Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology.

About Wham!

Can self-esteem be increased by playing a computer game called Wham? The answer is yes according to a study conducted by Jodene Baccus, a doctoral student in McGill’s Department of Psychology. Baccus, the lead researcher, collaborated with McGill graduate Dominic Packer (now a grad student at University of Toronto), under the direction of associate psychology professor Mark W. Baldwin. The team explains how computer games can enhance feelings of self-acceptance in the July edition of Psychological Science.Some 139 participants were recruited for the study, which began with a self-esteem measurement. Participants were then split into two groups: one played Wham! and another group played a placebo version. Participants who played Wham! entered into a computer some self-relevant information (e.g. first name, birthday). These identifiers would then flash on screen, be clicked (whammed) and be followed by a smiling face.

Baccus found that pairing a person’s personal information with the game’s positive social feedback helped enhance self-acceptance. “After playing Wham! for 10 minutes, the automatic and unconscious thoughts of participants was measured,” she says. “The result showed that players of Wham! had higher self-esteem than participants who played the placebo game.”

About EyeSpy: The Matrix

The McGill scientists designed EyeSpy: The Matrix to help change the habits of people with low self esteem, who often seem to expect rejection. In a forthcoming edition of the Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, Stéphane Dandeneau, a doctoral student, and Mark W. Baldwin, an associate psychology professor, explain how EyeSpy: The Matrix was created to train people to reduce their focus on non-acceptance.“We designed the game to teach players to seek the smiling or approving person in a crowd of frowning faces,” explains Dandeneau, who with Baldwin recruited 64 participants for the study. The researchers begun by measuring the self-esteem of each participant. Half of participants were then asked to play EyeSpy and half competed a placebo task. Using an attentional bias measure called the Rejection Stroop, the researchers demonstrated that the bias toward rejection among people with low self-esteem – versus subjects who completed a placebo task – was significantly lower for participants who completed EyeSpy.

“We found that EyeSpy: The Matrix teaches people, especially those with low self-esteem, the habit of looking for acceptance and ignoring rejection,” explains Dandeneau. “This could serve as an antidote to their usual habit of consistently looking for rejection information in their environment.”To sample Wham! or Eyespy: The Matrix, see our games page.

-30-

Reporters are welcome to use the images from this page.

Prepared text from press conference

Prepared text for Press Conference, May 6, 2004, McGill University.

Mark Baldwin

Stéphane Dandeneau

Jodene Baccus

Maya SakellaropouloBALDWIN:

Bonjour et bienvenue. Merci d’être venu.

My name is Mark Baldwin, and I am a psychology professor at McGill University. I will be speaking mostly in English today; in a few moments Stephane Dandeneau will try to balance that out by speaking mostly in French.

Today we are excited to tell you about the publication of two articles on self-esteem, that will be appearing in the coming weeks in prestigious, peer-reviewed psychology journals.

This research has shown that specially-designed computer games can help people build habits of thought that may improve their self-esteem.

Low self-esteem is unpleasant. I think we all know that how you feel about yourself is an important part of who you are, and your overall sense of wellbeing. Low self-esteem involves feeling insecure, unhappy with yourself, and dissatisfied with who you are.

It involves certain self-critical thoughts, such as thinking you are unworthy, or that you are inadequate or unlikable in some way.Many of us might like to boost our sense of self-acceptance and security, but sometimes it is not clear why we feel the way we do. Research has shown that low self-esteem results from certain habits of thought, many of which, at their core, involve worrying about rejection by others. Research has demonstrated that low and high self-esteem are produced by different habits of thought.

For example, imagine walking into a room full of people. If you have relatively low self-esteem you assume you do not have a lot to offer, so you may expect that you are going to be rejected. Because you are worried about this, you will be vigilant for rejection and your attention will be drawn to the one or two people in the room who seem to be scowling a bit. You may assume that their expression has something to do with YOU, and so you may spend time imagining different reasons why they are rejecting you. The more you think in this way, the more you create a link, so that every time you think of yourself, you think of being rejected. This becomes a vicious cycle: low self-esteem leads to an expectancy for rejection, which then reinforces your low self-esteem.

If you have higher self-esteem, you react quite differently. When you walk into the room you expect to be accepted, so your attention is drawn to the one or two people who are smiling warmly at you, and you end up interacting with them and ignoring or downplaying any negative feedback.

These are the kinds of thought processes that maintain people's level of self-esteem.

So why is it so hard to change these, and other negative habits of thought? Why can't people just decide to feel better about themselves? This is because the thought patterns become automatic. By this we mean that they happen very quickly and unintentionally, they are difficult to control, and they can even happen completely unconsciously.

There has been a fair amount of research over the past decade on trying to measure the automatic thought processes related to self-esteem problems, and we will be discussing some of those measurement techniques. Several previous studies by other researchers have shown that the thought processes assessed by these measures do correlate with phenomena of importance, including people's reactions to stressful situations, persistence in the face of failure, and so on.

We wanted to go beyond just measuring automatic habits of thoughts, to try to find ways to actually change them. Our research question, then, was whether we could help people directly modify their automatic habits of thought, to give them an enhanced sense of security.

We drew on our experience with computer games. Anyone who has played a computer game for hours on end knows that it can eventually start to change the way you think: A couple of hours playing Tetris, and before you know it you’re rearranging your closet. This is because you are doing the same mental act over and over again until it becomes habitual. We wondered if we could harness this same principle to help people change the way they think about themselves and their relationships to others.

As I mentioned, this research has been carefully reviewed by other scientists and has been accepted for publication in Psychological Science and the Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology. These are prestigious journals: Psychological Science is one of the top psychology journals in the world, and psychologists from around the world will be reading these findings in the coming weeks.

In a moment, Jodene Baccus will describe the game she researched, in which she tried to create a link between the self-concept and feelings of acceptance, rather than rejection. Stephane Dandeneau will describe a game in which he tried to reduce the vigilance for rejection that some individuals have. Each student will talk for about 5 minutes. Then I will have some final comments and we will take questions. But now we are going to ask Stephane to summarize quickly in French some of the main points I have just covered.

DANDENEAU:

Merci Mark. Bonjour, je m’appelle Stephane Dandeneau. Je suis Étudiant au doctorat sous la supervision du Docteur Baldwin. Je vais résumé l’introduction de Mark.

Plusieurs recherches ont démontré que l’estime de soi découle de certaines habitudes de pensées. Les habitudes de pensées associé à une faible estime de soi sont fondamentalement liées au rejet social.

Pourquoi est-il difficile de modifier les habitudes de pensées? Parce qu’elles sont automatiques, c’est-à-dire qu’elles sont des reflex de pensées qui surviennent souvent de façon inconsciente. Par exemple, quelqu’un d’optimiste voit automatique le côté positif d’une situation.

Plusieurs chercheurs ont trouvé des façons de mesurer les habitudes de pensées associées au problème de l’estime de soi. Nous allons décrire les mesures que nous avons utilisées dans notre recherche au cours de notre présentation.

L’important pour nous, cependant, est d’aller au delà de mesurer les habitudes de pensées et de trouver des manières de les modifier. Notre objectif de recherche est donc de développer des jeux à l’ordinateur qui pourrait modifier les habitudes de pensées liés à l’estime de soi.

Nous avons utilisé notre expérience avec les jeux d’ordinateurs comme modèle. Les personnes qui ont joué des jeux videos pour plusieurs heures savent comment leur façon de penser peut éventuellement changer. Quelques heures du jeu Tetris et vous avez le goût de réorganiser les meubles de votre salon! Cette habitude de pensée se développe à force de répéter un processus mental jusqu’à ce que ça devienne automatique. Suivant le même principe, nous nous sommes demandé si c’était possible de changer les habitudes de pensées liées à l’estime de soi.

Je passe maintenant la parole à Jodene, qui vous expliquera le jeu Wham! Conditionnez votre estime de soi.

BACCUS:

Merci Stephane et bonjour.My name is Jodene Baccus and I am a graduate student in Professor Baldwin’s research lab. I will be completing my PhD next year, and am very excited about the research we are presenting to you today.

I am going to talk to you about the Wham! Self-Esteem Conditioning Game. The Wham game increases self-esteem. It does this by linking together thoughts you have about yourself with thoughts of social acceptance. I’ll explain this further.

First, I’m going to clarify some of the principles underlying this research, then I will outline the methodology we used to gather data, and finally give you an overview of the findings.

First, some background information on self-esteem:

For this research, we looked at an aspect of self-esteem called implicit self-esteem. Implicit self-esteem is a self-evaluation that occurs unintentionally and outside of awareness. A person may not be intending to self-evaluate, or even be aware that they are making a self-evaluation. Implicit self-esteem is like a “gut feeling” reaction towards the self.

This differs from explicit self-esteem, which is a conscious self-report of how a person feels about him or herself. Explicit self-esteem is measured using questionnaires that contain items such as “I take a positive attitude towards myself” and “I feel I have a number of good qualities”. You can imagine that if you were filling out a questionnaire that included these statements you would probably be aware that your self-esteem was being assessed.

Implicit self-esteem, on the other hand, is measured in such a way that the person is not necessarily aware of what is being assessed.

One self-esteem measure, and one that we used in our research, is the Implicit Associations Test, called the IAT. The IAT was developed by other researchers about five years ago and is now the most widely accepted measurement tool for assessing implicit self-esteem.

The IAT looks at whether you find it easier to associate thoughts about yourself with good or with bad. For example, some people find it easy to associate themselves with negative thoughts. They have developed a habit where thinking of themselves automatically leads to a negative evaluation. It is easy for them to think of “self” and “bad” in the same category.

On the IAT, people are presented with words and asked to place them into one of two categories. In one category, they must place words related to the self (for example “me”, “my”) into the same category as words that are bad (e.g. “vomit”, “tragedy”). In the second category, they place words related to “other” or “good”. The IAT measures how long it takes people to classify the word. People with high implicit self-esteem will find it difficult to put “me” in the same category as “tragedy”, and so take a long time on these trials. People with lower implicit self-esteem do not find it so difficult to put me and tragedy in the same category, so are quicker.

Second – the game uses classical conditioning

Classical conditioning is a principle of learning. Some of you might be familiar with Pavlov’s study that first demonstrated classical conditioning.

Pavlov noticed that if a dog were presented with food, it would salivate. He then presented a tone that was followed by the presentation of food to the dog. The dog again salivated. Eventually, after repeated pairings, the dog would salivate when the tone alone was played. The tone and food had become associated to each other, thus producing the same response.

In the Wham! Game, self-relevant information is linked to positive social feedback.

Many of the core thought patterns underlying self-esteem involve interpersonal relationships. Positive thoughts and feelings about the self arise from the sense of being securely accepted and positively regarded by others. Thus, we devised a computer game to repeatedly pair self-relevant information with positive social feedback. Self-relevant information was the participant’s own name, birthday, hometown, street, ethnicity, and phone number. Positive social feedback consisted of photographs of smiling faces.

We thought that because smiling faces tend to be associated with acceptance, repeated pairing of the self with smiling faces would eventually lead to the self on its own triggering thoughts and feelings of acceptance.

To briefly outline the research paradigm:

139 McGill Undergrads and students from Dawson college in Montreal were randomly assigned to either the control or experimental version of the task

At the beginning of the session, all participants entered in some self-relevant information (e.g. name, birthday).

They were instructed that a word would appear in one of four quadrants on the computer screen, and their task was to click on the word using the computer mouse as fast as possible. They were also told that doing so would cause an image to be displayed briefly in that quadrant.

The words presented were chosen from those entered by the participant at the start of the session, as well as from a pre-programmed list of words fitting the same categories.

Experimental Condition

In the experimental condition self-relevant words were always paired with an image of a smiling face. Here is an example of how it looked.Control Condition

In the control condition a random selection of smiling, frowning, and neutral photographs followed both self-relevant and non-self-relevant informationParticipants saw the same number of smiling, frowning, and neutral photographs in both conditions. However in the experimental conditions, smiling faces were always paired with self-relevant information

The game went on for approximately 5 minutes.

Immediately following the game, we measured implicit self-esteem.

We also measured aggressive thoughts and feelings by having participants read some scenarios where they were playing a computer game against another person who insulted or rejected them. In this scenario, they were given the opportunity to blast their opponent with some loud noise.

We asked participants how loud and how long they would blast their opponent with the noise. I will return to this measure shortly.

ResultsResults showed that participants in the experimental condition, that is, those who saw their self-relevant information repeatedly paired with smiling faces over a period of about 5 minutes, had higher levels of implicit self-esteem when compared to those in the control condition. The game strengthened a habit of linking self with acceptance, and this lead to a higher level of implicit self-esteem.

There were also some intriguing results on the measure in which people imagined blasting someone who had rejected them with loud noise. We found that the game resulted in lower aggressiveness for a specific group of people. Participants who began the study low in explicit self-esteem reported less aggressive thoughts and feelings if they had played the experimental version of the game. The game seemed to lower the aggressiveness sometimes associated with low self-esteem. This is a preliminary finding and bears replication, however given recent suggestions that some video games increase aggression, we believe it is an important result

Overall, the Wham! creates an automatic expectation of secure social acceptance when thinking about the self.

It is important to note that in this study implicit self-esteem was measured immediately following the game. At this point, we cannot be sure of how long the effects last. We are just starting a study that will look at how long this boost to self-esteem might last and also to examine the effects of playing the game on a daily basis. Mark will talk more about future research in a few moments.

To end, I’ll leave you with the statement from the beginning:

The Wham game increases self-esteem. It does this by linking together thoughts you have about yourself with thoughts of social acceptance.

Stephane will be talking to you next about another game that our lab has developed. Thank you.

DANDENEAU:

Re-bonjour… je vais vous décrire le projet Ayez l’œil, sur lequel je travail depuis trois ans.Le fait d’être accepter ou d’être rejeté par d’autres personnes a un grand impacte sur nos sentiments d’estime de soi. Les personnes avec une basse estime de soi ont un passé de rejet social et anticipe le rejet social. Les personnes avec une haute estime par contre ont souvent plusieurs personnes qui les acceptent et se sentent acceptées.

Certaines personnes, notamment les ceux avec une basse estime de soi, sont très vigilant aux information de rejet social puisque cette information les dérange beaucoup. Les personnes avec un haute estime de soi ne sont pas vigilant au rejet.

Par exemple, quelqu’un avec une vigilance excessive au rejet social pourrait entrer dans une salle comme celle-ci et porter à regarder aux personnes qui froncent les sourcils ou qui expriment la désapprobation. Le fait d’être vigilant à ces visages renfrognés cause cette personne à être doublement plus affecté au rejet social parce qu’elle intériorise l’information à laquelle elle regarde.

Mais comment on peut mesurer la vigilance au rejet social?

Dans cette tâche, les participants sont demandés de nommer la couleur des mots qui apparaissent à l’écran le plus vite possible. Les mots qui sont présentés à l’écran sont de trois catégories, neutre (chaise), acceptation sociale (accepté), et de rejet social (rejeté).

Cette tâche implique donc d’abord le processus automatique de lire le mot, ainsi que le processus de nommé la couleur, ex. dire « jaune ». Si la personne est incapable d’ignorer le mot ou est très sensible au mot, elle va prendre plus de temps à nommer la couleur. Par exemple, si j’ai une basse estime de soi et que je suis très vigilant et très sensible au rejet social, je prendrais plus longtemps à nommer la couleur du mot « rejeté » que le mot « chaise » parce que je ne peux pas ignorer le mot « rejeté ».

Si quelqu’un est vigilant au mot, ils prendront plus de temps à nommer la couleur. Donc, les interférences Stroop sont créées lorsque le mot interfère avec le processus de nommé la couleur.

Nos recherches ont démontré que les personnes avec une basse estime de soi prennent plus de temps à nommer la couleur des mots relatifs au rejet social à comparé aux mots relatif à l’acceptation social. Ceci signifie qu’ils sont beaucoup plus vigilants au rejet social qu’à l’acceptation social.

Nous avons donc développé une tâche qui réduit cette vigilance excessive au rejet social.

Ayez l’œil : la matrice

Tout comme on peut développer l’habitude de prendre 10 grands soupirs lorsqu’on se sent stressé, on peut développer l’habitude d’ignorer le rejet social autour de nous.Le but du jeu Ayez l’œil est de développer l’habitude d’ignorer le rejet social afin de réduire sa vigilance excessive au rejet social. Excessive pas TOUT ignorer.

Comment ça fonctionne: Les instructions sont d’identifier le sourire dans la matrice de visages qui froncent les sourcils, et ce, le plus vite possible. À force de répéter ceci plus de 100 fois, cette tâche développe chez l’individu l’habitude mentale de « Cherche le sourire tout en ignorant le rejet autour de toi ».

La méthode de recherche que nous avons utilisé dans notre laboratoire est la suivante : d’abord nous mesurons l’estime de soi explicite des participants. Ensuite la moitié des participants ont complété la tâche Ayez l’œil, l’autre moitié une tâche contrôle. Après avoir terminé l’une des tâches de 5 minutes, on a utilisé la tâche des interférences Stroop pour mesurer la vigilance au rejet social.

Les résultats du test des interférence Stroop démontrent qu’après avoir joué au jeux Ayez l’œil, les personnes avec une basse estime de soi n’avait plus de vigilance au rejet social. Ils ont appris à ignorer le rejet social, ce qui a réduit leur vigilance à cette information.

Pourquoi est-ce que c’est important? Parce que ceci peut aider les personnes qui sont inconfortables dans des situations sociales ou qui ont peur d’interagir avec des groupes de personnes. Au lieu d’être constamment dérangé par des pensées de rejet social, ceci pourrait les mettre plus à l’aise puisqu’ils ne sont plus vigilants au rejet social.

Ayez l’œil est une sorte d’antidote à l’habitude de porter excessivement attention au rejet social.

Où allons-nous d’ici.

- Études à long termes: faire compléter la tâche plusieurs jours consécutifs.

- Combien de pratique faut-il pour que l’effet soit durable?

BALDWIN:L’estime de soi est très complexe, et nos recherches sont encore jeunes.

High self-esteem is, in some sense, a skill. And like any other skill, it requires practice. If you have ever taken up a new sport, or learned to play a musical instrument, you know that you have to practice a skill repeatedly until it becomes automatic. Practicing scales on the piano, for example, gradually builds the skills that enable you to play beautiful music. We suggest that in much the same way, secure self-esteem requires the practice of specific habits of thought, and that is what our games are designed to do. Most important are habits of thought that reinforce the experience of secure, accepting relationships with others. These thoughts may help people to turn the vicious cycle of low self-esteem around: Once people have positive expectations, they often become more likely to find positive social experiences, which can further nurture their self-esteem.

In the studies just described to you, we used standard assessment techniques from scientific psychology to measure people's automatic thought processes. These measures have previously been shown to correlate with social anxiety and other aspects of insecurity. When people played our games, their automatic thought processes were improved compared to other people who played a placebo game. We also found some beneficial effects on self-reports of aggressive feelings.

As Jodene and Stephane mentioned, we are now examining the effects of playing the games repeatedly over several days. Initial results indicate that playing one of the games led people, the next day, to have a reduced expectation of rejection by others. So, the initial results are promising.

We are only beginning to scratch the surface. It is important to stress that our games certainly do not replace the hard work of psychotherapy. Self-esteem develops over a lifetime of experience, starting with the person’s early relationships in childhood, and extending into adult circumstances, so it is not going to be easy to change. A person's level of self-esteem is MAINTAINED by certain habits of thought, though, so if those can be changed the person might be able to learn to be more self-accepting.

We plan to examine as many possible applications of these ideas as we can, and I believe that our continuing research will lead to new ways to help people.

We have already begun a project with salespeople, who deal with rejection everyday in their jobs. We also will examine whether the games might help children as they develop their own habits of thought.

With Maya Sakellaropoulo, the fourth member of our team, we are also developing another game, which you can see on our selfesteemgames website. In this game, called “Grow Your Chi”, you have a Chi Pet. Your job is to click on smiling faces and your name as they float by on clouds. If you click on enough smiles, your Chi Pet grows fur and becomes happy and fulfilled. Maya will be available afterwards to show you this game in action.

As I mentioned, we are thrilled about the upcoming publications, and we expect other researchers to be excited by our findings. These articles represent several years of hard work already: Stephane, Jodene and Maya are continuing to do a great job and so maybe we'll be back in a year or two with more findings to tell you about.

Thank you for your interest. Merci d'être venu.

© Mark Baldwin and McGill University 2004 - Copyrights and Disclaimer